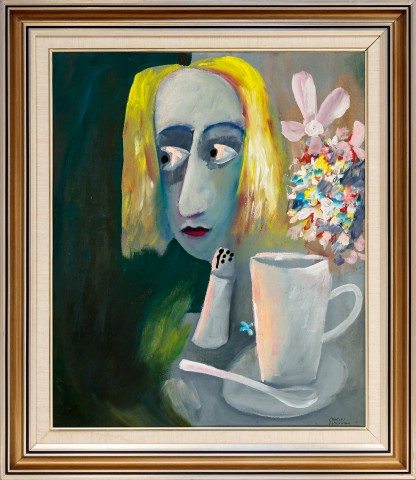

HEAD OF ALICE WITH CUP AND SAUCER, 1956

CHARLES BLACKMAN

tempera and oil on card on particle board

75.5 x 62.5 cm

signed lower right: CHARLES / BLACKMAN

bears inscription on frame verso: 6 Blackman

Joseph Brown Gallery, Melbourne

Private collection, Melbourne, acquired from the above in October 1978

Spring Exhibition 1978, Joseph Brown Gallery, Melbourne, 25 September – 9 October 1978, cat. 145 (illus. in exhibition catalogue, dated as c.1950)

Charles Blackman: Alice in Wonderland, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 11 August – 15 October 2006

Moore, F. St. J., and Smith, G., Charles Blackman: Alice in Wonderland, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2006, cat. 38, pp. 114, 115 (illus.), 140

240479 Blackman Alice Heide.jpg

Charles Blackman first encountered Lewis Carroll’s beloved children’s book, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in 1956. His introduction to the absurdist tale of fantasy and adventure was through a talking book which his wife, Barbara, who was legally blind, had borrowed from the library. While Blackman had heard of the famous story, he had never read it, and he later recalled:

‘I was absolutely thrilled to bits with it… and it seemed to sum up for me at that particular moment my feelings towards surrealism, and that anything could happen. The cup could lift off the table by itself, the teapot would… pour its own tea… The world is a magical and very possible place for all one’s dreams and feelings. One is completely outside of reality… This was sparked completely off by Barbara’s influence on my life.’1

While Carroll’s story was the initial impetus for Blackman’s Alice series, there were various other influences which fed into the evolution of its imagery. Working as a cook at the Eastbourne Café (better known in its later incarnation as Balzac restaurant) in East Melbourne, which was run by his friend, Georges Mora, Blackman drew the chairs, tables, teapots and crockery that became key motifs in the paintings. ‘I went to work… at 5pm… and… finished at 12 and then came home and my head was full of spinning plates and teacups and Barbara would say I brought the rabbit into the restaurant at night and… The restaurant came into the paintings.’2

240479 Blackman_Goodbye Feet, 1956_NGV.jpg

Blackman credited the vibrant colour of the paintings to the experience of painting outdoors with his friend, the artist John Perceval. Working in tempera and oil paint, he also acknowledged the influence of Perceval in his approach to making these works, describing them as ‘probably the freest pictures that I’ve painted… I’m not talking about the images, I’m talking about the actual way of painting. He was a wonderfully ecstatic painter… Perceval, very free and very beautiful.’3 Sidney Nolan and his now iconic series of paintings about the infamous bushranger, Ned Kelly, also played a part. Blackman had been impressed by Nolan’s art and his ability to ‘[trap] inner feeling in the paint’ and after attending the launch of the Kelly series in mid-1956, he was inspired to develop the Alice paintings into an extended series. Nolan also incorporated references to his own life into the Kelly paintings and this, in particular, struck a chord with Blackman who connected the miraculous transformation of Barbara (who was pregnant with their first child at the time) to Alice’s fantastic experiences, as well as Barbara’s increasing blindness and the spatial disorientation this caused.

In Head of Alice with cup and saucer, 1956, Alice’s head is separated from her body and appears to float in a strange and undefined space. Her face is framed by golden hair and her eyes, piercing and alert, look warily into the darkness. To her right a glorious bouquet of tiny flowers painted in lively daubs of red, yellow, blue and white paint, is topped with two larger but delicate blooms in mauve and pink. A small blue flower has dropped from the bouquet and is isolated between the pepper shaker and cup and saucer below – familiar accoutrements borrowed from the Mad Hatter’s tea party and Blackman’s place of work. Blackman scholar, Felicity St John Moore, describes the flower as ‘a breath of blue’ and identifies it as a reference to the artist’s soon to be born son.4

240479-(cleaned up).jpg

Blackman continued painting Alice pictures into early 1957 and they were launched at his exhibition, Paintings from Alice in Wonderland, which opened at the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Melbourne in mid-February that year. At the end of the brief ten-day viewing, five paintings had been sold and while the exhibition was far from a commercial success, it did attract considerable comment in the newspapers. Arnold Shore was the most enthusiastic, writing that ‘Salient incidents… are freely interpreted and the artist’s purpose is to suggest the magical topsy-turvy world which the heroine met in her journey through wonderland.’5 Shown again in the late 1960s, by which time Blackman had established a significant reputation in London and at home, the response was unreservedly positive. Writing in the Brisbane Courier-Mail, Gertrude Langer declared, ‘I feel certain these paintings will live when much that is now fashionable is forgotten. The impression this exhibition as a whole makes is overwhelming… Everything looks spontaneous and just born of inspiration, yet analysis reveals a fine wisdom of picture-making.’6

With examples now represented in major private and public collections across the country, the Alice in Wonderland series represented a significant turning point in Blackman’s career. Alice was a subject that, in his words, ‘allowed me to paint in a totally different style. [To believe] that anything is allowable.’7

1. Charles Blackman in ‘Interview with Robert Peach’, Sunday Night Radio Two, ABC Radio, 9 September 1973, cited in St John Moore, F., ‘Conception to Birth: The Alice in Wonderland Series’ in St John Moore, F. & Smith, G., Charles Blackman: Alice in Wonderland, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2006, p. 10

2. Charles Blackman, cited in Shapcott, T., The Art of Charles Blackman, Andre Deutsch, London, 1989, p. 23

3. Charles Blackman, cited in Shapcott, ibid., pp. 23 – 24

4. St John Moore, op. cit., p. 114

5. Shore, A., ‘Painter in Alice’s Wonderland’, Age, Melbourne, 12 February 1957, p. 2

6. Langer, G., ‘Blackman’s Genius in his “Alice” Series’, Courier-Mail, Brisbane, 7 September 1966, p. 2, cited in Smith, G., ‘Which Way, Which Way? The Production and Reception of Alice in Wonderland’, St John Moore, 2006, op. cit., pp. 29 – 30

7. Amadio, N., Charles Blackman: The Lost Domains, A. H. & A. W. Reed, Sydney, 1980, p. 25

KIRSTY GRANT