FLOW, 2002

BRONWYN OLIVER

copper

80.0 cm diameter

Private collection, New South Wales, a private commission from the artist in 2002

Bronwyn Oliver, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, 21 November – 14 December 2002

Fink, H., Bronwyn Oliver: Strange Things, Piper Press, Sydney, 2017, pp. 145, 148 (illus.), 149 (illus.), 220

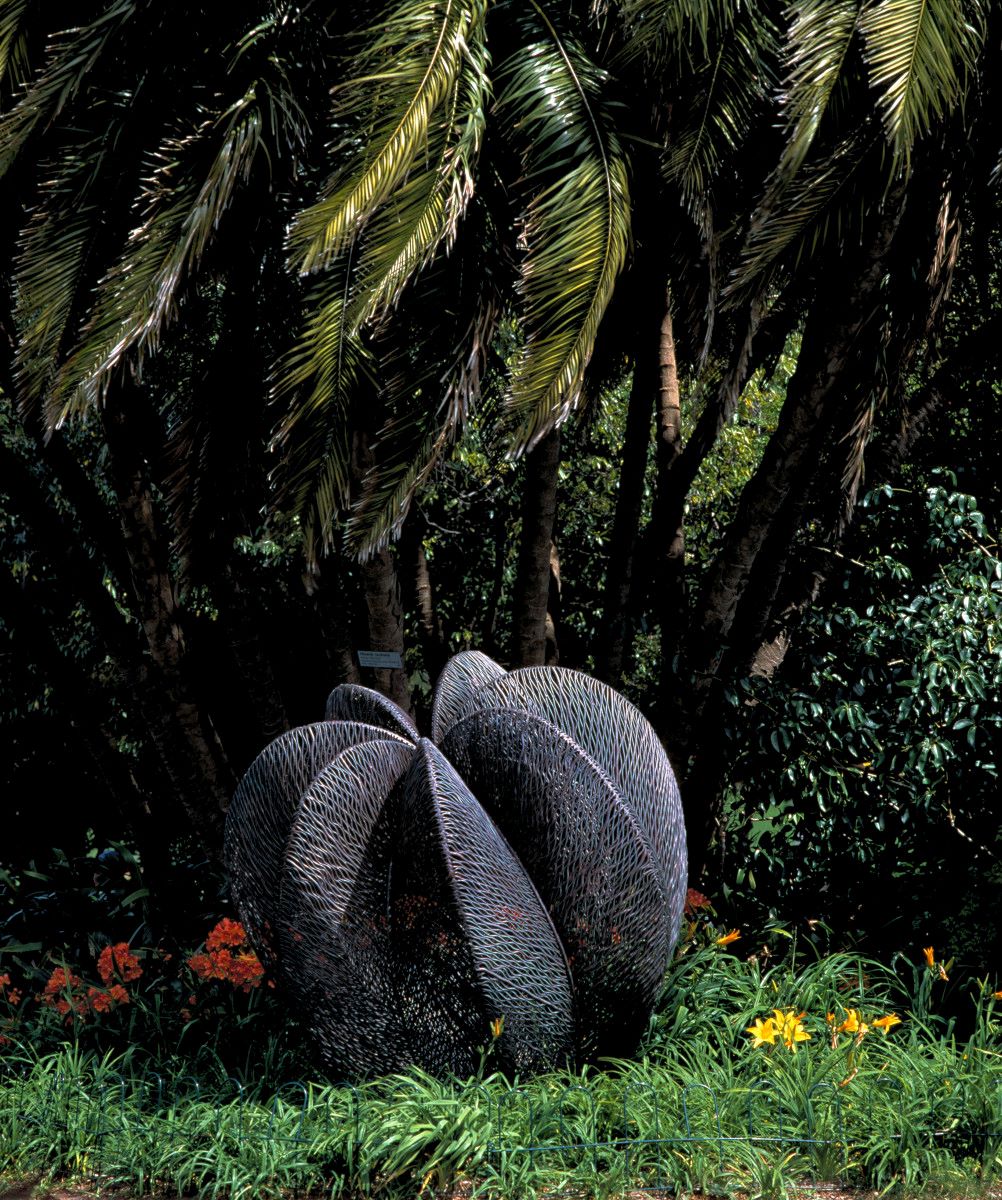

Flow in situ in the garden at Jamberoo House, New South Wales

|

Flow in situ in the garden at Jamberoo House,

New South Wales

photographer unknown

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy of Roslyn

Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

|

A large swirling orb, with fluid bristles and filaments emanating from its surface, the aptly titled Flow, 2002 echoes the joyful organic rhythms and structures that govern the natural world within which it was placed. Described as ‘perhaps Oliver’s most successfully realised garden work’1, Flow was commissioned privately at the height of the late sculptor’s fame, in the first years of the new millennium, a period during which her work was dominated by two essential hollow forms: the sphere and the ovoid. In 1999, Oliver received her first major sculptural commission from the City of Sydney, for which she created a pair of oversized seed forms made of welded copper, Palm and Magnolia (Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney). Following the public success of these sculptures, in the early 2000s, she experienced a flurry of private commissions. For many of these, she proposed a series of unstable orb-like forms with filigreed carapaces realised in monumental dimensions when installed outdoors, with others retaining an intimate and domestic scale. Flow, realised with a skilful smooth manipulation of individual copper rods, each terminating abruptly in a small bulb, is amongst Oliver’s most fluid and self-assured compositions.

‘The structure of the sphere should echo the vitality of the growth around it. This sphere has a gently spiralling density. From within the structure, a profusion of hairs emerges, each with a blunt tip which curves around the spiral but remains within the fibrous husk of the form. The lichen on the garden bench has a kind of woolliness. There is a very delicate texture of fuzz in the tiny vine spreading over the tree leading down to the garden and the grasses are hairy and shaggy. This hairy growth habit became the subject for sculpture and the sphere seemed the natural form.’2

Bronwyn Oliver Globe, 2002

|

Bronwyn Oliver

Globe, 2002

copper, 250.0 cm diameter

University of New South Wales, Sydney

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy of Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

|

Understanding Flow within the context of the above artistic rationale, supplied to the present owners alongside a maquette and proposal ahead of the commission, the relationship of poetic associations with the sculpture’s intended garden site becomes clear. Oliver continually denied any overt naturalistic inspiration in her work, occasionally explaining that any organic associations would have arisen naturally from her post-modern practice learned at the Chelsea School of Art, which was grounded in the action of creation and infused with profound respect for materials. The ‘hairs’ that create the surface of Flow’s orb, loosely and organically follow the pattern of magnetic radiation between two poles, becoming longitudinal lines emanating from the northernmost pole before converging at its base.3

Although many of Oliver’s commissions from this period had smooth closely woven surfaces and smooth profiles, such as Core, Orb and Globe, Flow’s contours are uniquely rippled, its regular undulations echoing the overlapping branches of trees and creating an enticing tactile quality. This is an unusual form, with Oliver’s usual copper wire not woven into a web of intersecting fenestrations, but instead kept intact in long threads of copper wire (of a uniform gauge) loosely combed together in flowing strands. As Graeme Sturgeon noted, as early as 1991, the structural principles that determine Oliver’s forms can be distilled to the consistent actions of ‘spiralling, wrapping, binding, swelling, expanding and stretching’4, all processes of becoming or clear movement, often clearly repeated in the sculptor’s concise choice of title with emphatic one-word verbs, such as Flow.

Bronwyn Oliver Palm, 1999

|

Bronwyn Oliver

Palm, 1999

copper, 190.0 x 180.0 x 180.0 cm

Royal Botanic Garden, Sydney

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy of

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

|

Although its imposing dimensions ensure the sculpture maintains its own integrity within a densely vegetated outdoor setting, Flow’s hollow interior and open form fret-work allow for modest transparency and for the work, in the right atmospheric conditions, to ‘appear filled with light.’5 Flow was created specifically for Rob and Robin White’s country residence, Jamberoo House, to be nestled in the valley below the award-winning house designed by Glenn Murcutt. Intended to become a collaborative presence within the garden, Flow reflects and emulates the contours of the surrounding animate and inanimate objects, perched on a boulder beside a staircase hewn into the rock.

One of Australia's most highly regarded contemporary sculptors, Bronwyn Oliver remains celebrated for her extraordinary ability to produce meticulously articulated works of immense beauty and grace which unite timeless, organic forms of the natural world with the abstract logic of geometry. Oliver's delicately woven and enduring copper forms continue to surprise and inspire – their enigmatic presence beguiling both the eye and the mind.

1. Fink, H., Bronwyn Oliver. Strange Things, Piper Press, Sydney, 2017, p. 145

2. Artist’s rationale, 2002, reproduced ibid.

3. With the neat flatness of these poles, Oliver has (perhaps unknowingly) illustrated a mathematical theorem of topology colloquially known as the ‘Hairy Ball Theorem’.

4. Sturgeon, G., Contemporary Australian Sculpture, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1991, p. 73

5. Although speaking of another contemporaneous commission in Massachusetts, Orb, the same effect has been created with Flow.

LUCIE REEVES-SMITH