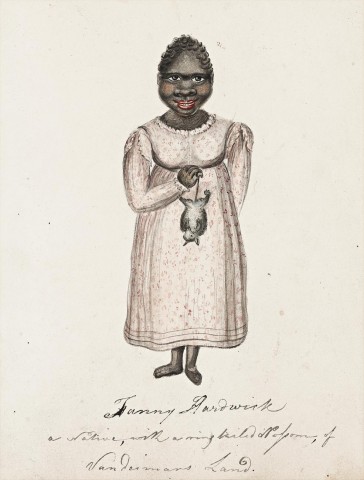

FANNY HARDWICKE: A NATIVE WITH A RINGTAILED POSSUM, VAN DIEMEN’S LAND, c.1822 – 24

Attributed to FREDERIC HARDWICKE

ink and watercolour on paper

27.5 x 22.0 cm

inscribed with title lower centre: Fanny Hardwick [sic] / a native with a ringtailed possum, of / Van deimans [sic] Land.

Private collection

Leonard Joel, Melbourne, 7 November 1979, lot 99

Ken and Joan Plomley Collection of Modernist Art, Melbourne

Plomley, N.J.B (ed.), Friendly Mission: the Tasmanian journals and papers of George Augustus Robinson, 1829-1834, Tasmanian Historical Research Association, Bellerive, Tasmania, 1966, p. 105

Anderson, S., Charles Browne Hardwicke: an Early Tasmanian Pioneer, Wentworth Books, Sydney, 1978, pp. 60, 61 (illus.), 63

Fletcher, M., Costume in Australia, 1788-1901, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1984, pl. 6 (illus.), p. 31

Broadbent, J., and Hughes, J. (eds), The Age of Macquarie, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1992, p. 151 (illus.)

Kerr, J. (ed.), The Dictionary of Australian Artists: Painters, Sketchers, Photographers and Engravers to 1870, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1992, p. 347 (illus.)

Coleman, D., Romantic Colonization and British Anti-Slavery, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2005, fig. 14, pp. 196 (illus.), 197 – 98

Other examples of this print are held in the collections of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney; and the Ballarat Fine Art Gallery, Victoria

The separation of indigenous children from their families and their institutionalization or adoption by Europeans is a familiar colonial-ethnocidal practice. The existence of such abuses in the Australian setting is well-known, being most recently and most comprehensively documented in the Bringing them home report.1 They were certainly commonplace in early settler Van Diemen’s Land – indeed, well before the Black War of the late 1820s, we find Lt-Gov. William Sorell making reference to the ‘Outrages of Miscreants … who sometimes wantonly fire at and kill the Men, and at others pursue the Women for the purpose of compelling them to abandon their Children…’.2 At the 2019 Dark Mofo festival, as part of the outdoor exhibition Dark Path, contemporary Trawlwoolway artist Julie Gough presented a haunting installation entitled Missing or Dead. This work – comprising ‘wanted’ posters attached to trees in the bush of the Hobart Domain – documents the lives of 185 Tasmanian Aboriginal stolen children whose traces Gough has been able to find in settler archives.

In addition to written records, the tragic lives of these orphan First Nations children of Van Diemen’s Land are recorded in two poignant watercolour portraits. One is Thomas Bock’s well-known image of Mathinna, a Lowreenne girl born in exile on Flinders Island in 1835. She was ‘given’ to Lt-Gov. Sir John Franklin and his wife in 1840, only to be abandoned to the Queen’s Orphan School when the vice-regal couple returned to England three years later. Bock’s drawing shows the ‘unconquerable’3 seven-year-old wearing a ‘red frock. Like my father’,4 but with bare feet.5

The present work, though obviously not as carefully-observed or technically adept as Bock’s, has a comparable historical significance and a similar affective power. Like Mathinna, Fanny Hardwicke is doll-dressed in European clothes – in this case an empire line printed muslin day dress, with capped long sleeves and a triple-tucked hem. She, too, is without shoes. However, it is not the pathos of a barefoot black child in a cast-off English dress that gives this work its appeal, but rather the evident strong character of the sitter. Fanny’s gaze is direct and open, and her cherry-lipped mouth smiles warmly at the viewer. In her right hand she holds by the tail what is evidently a pet, but which also serves as a sign of her Aboriginality: a little ring-tailed possum (Pseudocheirus peregrinus).

Although the name Frances was not uncommon in this period, and there has been some confusion between the several Indigenous Fannys that appear in the archive,6 it seems likely that Fanny Hardwicke is the sealer’s woman interviewed by George Augustus Robinson in the Hobart Town Gaol in October 1829. Robinson’s journal describes ‘Fanny, who speaks English well and knows not a word of the aboriginal tongue,’ clear evidence of a settler upbringing, though she evidently retained the native name Mitteyer. Robinson also notes ‘that she could navigate a schooner, could hand reef and steer. In make she was of middle stature, strong and very robust, and of quick intellect; and had been baptised by a clergyman at Launceston, Reverend Youl’.7 Originally a Trawlwoolway from Ringarooma, at the time of her meeting with Robinson, Fanny was the companion of a Bass Strait sealer named Baker, later living and working with ‘Norfolk Island Jack’ Williams, both at the Kent Group and on Kangaroo Island.

The northern Tasmanian settler who presumably raised the girl was Charles Hardwicke, a former Royal Navy officer who arrived in Sydney on the infamous General Hewart voyage of 1814.8 Granted permission to remain in the colony and awarded a land grant of 200 acres, Hardwicke established a successful pastoral venture at Norfolk Plains (Longford).9 According to a descendant, ‘Hardwicke extended kindness to the native Tasmanians, and had one of them in his home as a servant, and sought to educate and train her’.10

The drawing is evidently the work of an amateur, and in Joan Kerr’s Dictionary of Australian Artists… it is attributed to Hardwicke himself.11 However, it is worth noting that Charles’ younger brother Frederic, who arrived in the colony in 1822, was at least something of an artist; Charles’ chart of his maritime expedition from Port Dalrymple to North West Cape in that same year is illustrated with three landscape sketches by Frederic.12 It is here proposed that Frederic is the artist of the present work.

1. Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 1997

2. ‘Government and General Orders’, Hobart Town Gazette and Southern Reporter, Hobart, 13 March 1819, p. 1

3. The adjective is Lady Franklin’s, from a letter to her sister of February 1843, quoted in Kolenberg, H., ‘Unconquerable spirit’, in Thomas, D. (ed.), Creating Australia: 200 years of art 1788-1988, International Cultural Corporation of Australia/Art Gallery Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1988, p. 95

4. Letter to Lady Franklin 14 November 1841, transcribed by Mathinna’s adoptive sister Eleanor Franklin, National Library of Australia, Gell and Franklin family papers 1800-1955 (Australian Joint Copying Project), Reel M379

5. The fragmentary letter also says ‘I have got sore feet and shoes and stockings.’ In a classic piece of cultural sublimation, for many years the drawing was housed in an oval mount which obscured the child’s obnoxious pedal extremities.

6. Two others are listed by N.J.B. Plomley from the journals of George Augustus Robinson: an adolescent girl who died in 1831 and Wutapuwitja (Wortabowidgee), also known as ‘Jock’, who was the wife of Tunnerminnerwait (‘Jack’), one of Robinson’s ‘friendly natives.’ Curiously, the eldest child of Charles Hardwicke, Fanny’s presumed adoptive father, was also named Frances (b. 1820).

7. Plomley, N.J.B., (ed.), Friendly Mission: the Tasmanian Journals and Papers of George Augustus Robinson 1829-1834, Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery/Quintus Publishing, Launceston, second edition, 2008, pp. 91 – 92. Baptismal records show that Rev. Youl baptised a ’native child of about eleven years of age’ on 12 January 1820. Church Registers of the Anglican Parish of St John’s, Launceston, Archives Office of Tasmania, NS748/1/3

8. See Bateson, C., The Convict Ships, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 2004, pp. 198 – 199

9. By 1829 his landholdings had expanded to a total of 3,000 acres; he is today largely remembered as a pioneer of horse-breeding and racing in Tasmania. See Pretyman, E.R., 'Hardwicke, Charles Browne (1788–1880)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hardwicke-charles-browne-2154/text2751, published first in hardcopy 1966, accessed online 13 July 2019.

10. Anderson, S., Charles Browne Hardwicke: an Early Tasmanian Pioneer, Wentworth Books, Sydney, 1978, p. 63

11. Kerr, J. (ed.), The Dictionary of Australian Artists: Painters, Sketchers, Photographers and Engravers to 1870, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1992, pp. 346 – 7. Kerr’s even more determinedly feminist online successor, Design and Art Australia Online suggests the drawing may be by Charles’ wife Elizabeth (née Chapman). See https://www.daao.org.au/bio/charles-browne-hardwicke/ (accessed 16 July 2019)

12. Archives office of Tasmania, 343/1/3. Frederic’s technical understanding is illuminated in a remark in a letter from his brother to Lt-Gov. Sorell: ‘My brother … begs me to assure your honour that he is sorry for not being able to furnish some views he had taken, by this conveyance, for the want of two or three particular colours, but hopes soon to be able to send them.’ Letter, 23 January 1824, quoted in Anderson, op. cit., p. 35

Dr David Hansen

Associate Professor, Centre for Art History and Art Theory, School of Art and Design, Australian National University