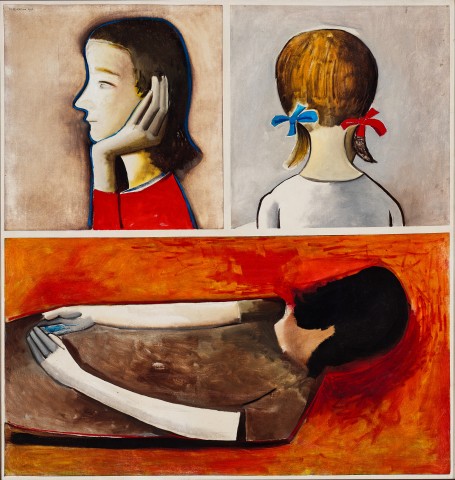

DOUBLE IMAGE, 1961

CHARLES BLACKMAN

oil on canvas on composition board

126.5 x 120.0 cm

signed and dated upper left: BLACKMAN 1961

MEPC Australia Ltd collection, Sydney

Savill Galleries, Sydney (label attached verso)

Company collection, Sydney

Deutscher~Menzies, Melbourne, 20 August 2001, lot 39

Company collection, Melbourne

Deutscher~Menzies, Sydney, 15 June 2005, lot 35

Private collection, Melbourne

probably Paintings and Drawings by Charles Blackman, The Matthiesen Gallery, London, 3 – 25 November 1961

A Salute to Charles Blackman, Savill Galleries, Sydney, 12 August – 5 September 1998, cat. 7 (illus. in exhibition catalogue)

‘…Part of their essential character springs from the interpretation, marvellously developed and sustained, between the tenderness and grace of the personages contained in the paintings and the fiercely implacably controlled means taken to give these personages life and eloquence within the terms of painting itself…’1

At the time of unveiling his seminal solo show at Mathiesen Gallery in London in November 1961 (in which Double image, 1961 was most likely included), Charles Blackman’s star was in the ascendent. In 1958, one of his Alice paintings had been acquired by the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris (a remarkable feat for any Australian artist), and in June 1960, his solo exhibition at the Johnstone Gallery had completely sold out, realising approximately 4,500 pounds and enabling the Blackmans to buy a house in St Lucia, Queensland. Two months later he was awarded the prestigious Helena Rubinstein Travelling Art Scholarship for his celebrated Suites I – IV (now housed in the collections of the state galleries of New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia), and by the following February, he and his family had relocated to London where they would remain for the next five years. In June 1961, three of his paintings were featured in the groundbreaking Recent Australian Painting exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London, alongside major works by Boyd, Nolan, Tucker and Whiteley, and later that year, he was selected, together with Whiteley and Lawrence Daws, to represent Australia at the progressive Biennale des Jeunes organised by the Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris.

An impressive achievement both in scale and conceptual breadth, Double image comprises one of a select few works created during this pivotal period in Blackman’s oeuvre when, stimulated by the dynamic European art scene, he was at the height of his artistic powers and critical success. As one London newspaper critic observed of his representation at the Whitechapel show, ‘The most moving – and the discovery of the exhibition – are the three remarkable paintings by Charles Blackman… It is fanciful to see in this painting not only a new and original talent but a sign that Australian painting is at last moving away from its obsession with the outback?’2 Meanwhile, English art critic Bryan Robertson, an early champion of the young Antipodean’s work, was so impressed that he offered to arrange the subsequent solo exhibition for Blackman at the Mathiesen Gallery, writing in the Preface to that catalogue: ‘These are some of the strongest, most urgent and forceful paintings by a young artist that I have seen in the past ten years.’3

As Robertson continued: ‘…We are given a curious impression, often of a double image, positive and negative, as well as of the space between people… The formal roots of Blackman’s paintings extend beyond the Renaissance to Byzantium. He has made icons from the commonplace material of domestic life. The fragile gestures and spontaneous movements among people in the streets around us are caught and made eloquent...’4 Separated into three voyeuristic vignettes akin to a split-screen ‘suite’, the present composition is populated entirely by female forms in various poses and guises – one silhouetted in bright light with hand cupped to her ear to aid her hearing, a second with back turned and the tender nape of her neck exposed, and the third lying prostate, face obscured, across the lower half of the canvas. Tough yet tender, firm of outline but fragile of psyche, it is difficult to know whether the work represents separate figures, or one and her shadows (psychological or emotional, rather than physical) – with each of the three gestures plausibly alluding to his wife Barbara and her encroaching blindness. Imbued with an aching sense of loneliness and curious, almost existential quality, indeed the work thus typifies brilliantly the formal, iconographic and emotional ambiguity of these early London pictures which brought Blackman such acclaim – his enigmatic dreamworld offering a rich matrix for the viewer’s imagination, for what Ray Mathew called ‘introspection distanced… by identification with others.’5

1. Robertson, B., ‘Preface’, Charles Blackman: Paintings and Drawings, The Mathiesen Gallery, London, 1961, n. p.

2. Pringle, J.D., ‘The Australian Painters’ in Observer, London, 4 June 1961, n. p.

3. Robertson, op. cit.

4. ibid.

5. Mathew, R., ‘London’s Blackman’, Art and Australia, Sydney, vol. 3, no. 4, March 1966, p. 283

VERONICA ANGELATOS