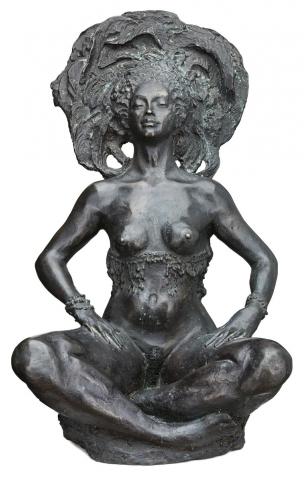

BALINESE DANCER, c.1927

NORMAN LINDSAY

cast 1984

bronze

58.5 cm height

stamped at base: National Trust NSW Bronze Sculpture Workshop

Lawsons, Sydney, 21 July 1992, lot 174

Private collection, Sydney

Rowlison, E.B., 'Olympus at Springwood: The Sculpture of Norman Lindsay', Art and Australia, Sydney, vol. 11, no. 2, October–December 1973, pp. 160–167 Hope, A.D. (introduction), Siren and Satyr: the personal philosophy of Norman Lindsay, Sun Books Pty Ltd, Melbourne, 1976, p. 57 (illus. cement version, as 'Oriental Woman')

Smith, M., 'Bronze-age protection for sculptures', Sydney Morning Herald, 14 June 1984, p. 39

Oriental Woman, c1927, cement, 66 cm height; Balinese Dancer, c1984, bronze, 65 x 30 cm, both in the Norman Lindsay Gallery and Museum, Springwood, New South Wales

Painter, etcher, draughtsman, maker of model ships, writer - Norman Lindsay's outrageous fame in many areas overshadowed his achievements in others, especially sculpture. For some he is the masterful creator of buxom beauties and bellicose buccaneers, or gifted author of such comic fantasies as The Magic Pudding. For others it is the incisive line of his etchings and cartoons for The Bulletin, remembered vividly for World War I images of the ogre of German militarism. His first model ship, Captain Cook's Endeavour, found its way into the collection of the Melbourne Museum by way of the Felton Bequest and the National Gallery of Victoria. Model making was, for Lindsay, a means of relaxation away from the studio. It was the same for sculptures, made for personal pleasure. Although he once said he did not take them too seriously, he added 'but they make nice garden ornaments.'1 The first and following sculptures were made in the gardens of his home at Springwood in the Blue Mountains - sirens, satyrs, nymphs, nudes, a seahorse fountain, and the Sphinx of Greek mythology. As in his many other works, his wife Rose provided a splendid model for the nymph in Satyr pursuing Nymph c1913. Set in garden and bush surrounds, pantheistic of mood, most were made between 1913 and 1940, though Lindsay continued making sculpture into later life.

Following the 1924 alterations, additions, and a courtyard to the Springwood house, the cement version of Balinese Dancer was placed within the courtyard, the main entertainment area.2 In an article on Lindsay's sculpture, Eric Rowlison, one-time director of the National Gallery of Victoria acclaimed the work - 'This beautiful figure, one of Lindsay's finest sculptures, is virtually unknown to the public as a theme in his work. But she is not unique. She appears again as the subject of several other sculptures and at least one oil and, in profile, on a pair of book-ends - all of the foregoing in private collections.'3 The gods so richly endowed Lindsay that he could spread his talents across a wide field with unwavering success. Using the unappealing medium of cement, he dabbed it wet on to metal armatures to support his forms. In all this drab greyness, the ability of his siren ladies to seduce is but another example of the marvels that were Norman Lindsay. Between 1984-87, the National Trust of New South Wales undertook, for preservations purposes, the bronze casting of some of these sculptures for outside display, moving the cement versions inside the Lindsay Museum. Sculptor, John Gardner made the moulds for the casting, Balinese Dancer being the first. A small edition of the work was cast at this time.

1. Lindsay quoted in Scarlet, K., Australian Sculptors, Thomas Nelson Australia Pty Ltd, Melbourne, 1980, p. 382

2. Rowlison, E.B., 'Olympus at Springwood: The Sculpture of Norman Lindsay', Art and Australia, Sydney, vol. 11, no. 2, October "December 1973, p. 160, courtyard illus.; also illus. p. 166, titled 'Oriental Woman'. As the original sculptures were not named formally, variations do occur.

3. Ibid, p. 163

DAVID THOMAS