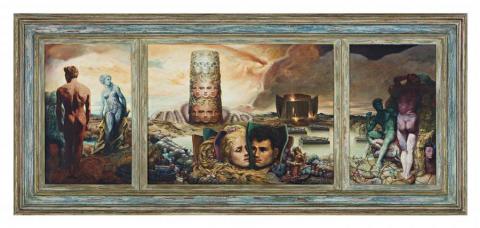

TRISTAN, 1952

James Gleeson

oil on canvas (triptych)

53.5 x 33.0 cm, 53.5 x 71.0 cm, 53.5 x 33.0 cm

signed and dated lower right: GlEESOn / 52 inscribed verso on frame: "TRISTAN" 1400 gns /James Gleeson / 10 Tarakan Cres., / Northbridge

housed in the original artist's frame

Private collection, Sydney, acquired directly from the artist, 14 April 1955

Archibald, Wynne and Sulman Prizes 1952, National Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 24 January - 8 March 1953, cat. 17

Contemporary Australian Paintings: Pacific Loan Exhibition, on board Orient Line S.S. Orcades, Sydney, 2 October 1956; Auckland, 8 October 1956; Honolulu, 16 October 1956; Vancouver, 22 October 1956; San Francisco, 25 October 1956; National Art Gallery, Sydney, November 1956 (label attached verso)

James Gleeson: Beyond the Screen of Sight, Ian Potter Centre, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 29 October 2004 - 27 February 2005; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 18 March—13 June 2005 (label attached verso)

By Our Art Critic, 'Archibald Show “Worst In Memory”', Sydney Morning Herald, 24 January 1953, p. 2

Contemporary Australian Paintings: Pacific Loan Exhibition: an exhibition arranged by the Orient Line in collaboration with the National Gallery Society of New South Wales: accompanying the exhibition Mr James Gleeson, artist, critic and lecturer, Shepherd Press, Sydney, 1956, cat. 37

Free, R., James Gleeson, Images from the Shadows, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1993, p. 94. pl. 24a (illus.)

Klepac, L., James Gleeson: Beyond the Screen of Sight, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2004, pp. 116 (illus.) and 117 (illus., detail)

The tale of Tristan and Isolde had a particular appeal for James Gleeson, who painted a number of versions of the subject culminating in the grand triptych of 1952. Influenced by Richard Wagner's opera, which he had seen in Sydney in 1935, he made a number of drawings during his sea voyage to London in 1947. These led to the painting Sea-Wrack Involving the Heads of Tristan and Isolde completed in that year, introducing a number of ideas images found in our painting. In the nineteenth century the great medieval tale of Tristan and Isolde attracted such artists as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Sir Edward Burne-Jones and Frederick Lord Leighton through its romantic and dramatic appeal, providing an ideal narrative for images of courtly love. By contrast, as Renée Free has pointed out, 'In Sea-Wrack Involving the Heads of Tristan and Isolde Wagner's music and the subject matter match the artist's psychic state.'1 This continued in Tristan, a major painting of the time. When included in the 1952 Sulman Prize exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, it was given special mention by the art critic for The Sydney Morning Herald as one of the '...two outstanding paintings for the Sulman Competition...'2

Wracked with shame, betrayal and guilt, the story of Tristan and Isolde hinged on their accidental drinking of a love potion that made the heroic Tristan, the chosen knight of King Mark, fall in love with his master's bride-to-be, leading to adultery and deception. The added power of Wagner's music provided Gleeson with intoxicating inspiration, the voyage to London by ship giving him the sea setting, which begins and concludes Wagner's music drama.

During the early 1950s Gleeson was absorbed in Neoplatonism and Michelangelo, influences that changed the course of his art. They are clearly apparent in the Tristan. Gleeson's visit to Italy in the summer of 1948 had 'a tremendous influence... The Michelangelo experience- the Platonic idea of man's beauty reflecting goodness' dominated. This was reflected in the style change mid-century. I read a book about whether the human being is capable of perfection. I believed Michelangelo and the Platonists for a while and later rejected it.'3

In Tristan, the triptych format elevates it by association with Christian altarpieces, many of which Gleeson would have seen during his Italian sojourn. Michelangelesque in musculature and grandeur, the leading role played by the nude male figure is clearly drawn from his Florentine- Roman experiences. Its precursor is the almost autobiographical painting Italy 1951 in the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Redolent of the journey, of classical architectural order and ancient ruins of disorder, the sculptural and the ideal, and real male and female figures reappear in Tristan. In both paintings the artist is present in several guises. While the golden locks of Isolde are appropriately decked in bridal flowers and pearls, the figures and faces represent projections of the anima and the ego. Of self-identification and guilt, portraits of the ill-fated lovers are encapsulated within shards in a painterly exploration of the intertwining of myth and the psyche. A major painting of its time, Tristan is Gleeson at his characteristic best in the interplay of ambiguity and the double-edged.

1. Free, R., James Gleeson: Images from the Shadows, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1996, p. 26

2. By Our Art Critic, 'Archibald Show' "Worst I Memory'', Sydney Morning Herald, 24 January 1953, p. 2

3. James Gleeson quoted in Free, op. cit., p. 29

DAVID THOMAS