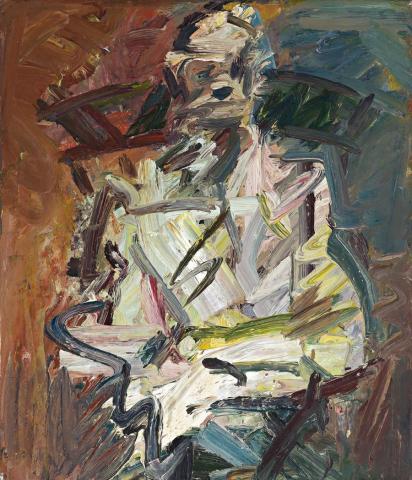

DAVID LANDAU SEATED, 1992

FRANK AUERBACH

oil on canvas

71.0 x 61.0 cm

Marlborough Fine Art, London (label attached verso)

Private collection, Sydney

Liverpool Street Gallery, Sydney (label attached verso)

Private collection, Adelaide

The Collectors Exhibition, Liverpool Street Gallery, Sydney, 19 February – 17 March 2005

On loan to Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide (label attached verso)

Feaver, W., Frank Auerbach, Rizzoli, New York, 2009, cat. 685, p. 317 (illus.)

In 1956, art dealer Helen Lessore at the Beaux-Arts Gallery in London, gave Frank Auerbach his first solo exhibition. By this time, Auerbach, who was sent to Britain from his birthplace in Berlin at the age of seven to escape the Holocaust (which claimed the lives of both parents), had set the direction for his remarkable life as an artist. At sixteen he left Bunce Court, a progressive boarding school in Kent, and abandoned his ambition to become an actor after winning a place at St Martins School of Art in London. There he met fellow artist Leon Kossoff. Auerbach was also, at the time, taking lessons from the influential painter David Bomberg when he suggested Kossoff join him, and so began a lifelong friendship and artistic bond. Bomberg encouraged Auerbach to study the work of Paul Cézanne and it was then he developed his technique of layering vast amounts of paint. Commenting on the 1956 Beaux Arts exhibition, art critic, David Sylvester enthused, 'Auerbach ... has given us, at the age of twenty four, what seems to me the most exciting and impressive first one man show by an English painter since Francis Bacon in 1949.1

All great artists create their own unique visual language and methods of working. Frank Auerbach's is particularly intense and complex. He famously used to take only one day's holiday a year, travelling down to Brighton and back. His life revolves around his studio in Camden. He even sleeps there most nights and rises at dawn, when night-clubbers are emerging into the weak north London light, to draw his immediate surroundings. But it is the portraits that matter most. He will have up to a dozen of them under way at any one time. His handful of loyal sitters (mainly family members, writers and curators and close friends) arrive for a few hours each week, year after year, sometimes decade after decade.

Originally a medical doctor, former Chairman of the National Gallery Company, London, and founder of Print Quarterly, Dr David Landau, portrayed in this classic work, wrote to Auerbach in 1983 wishing to commission a portrait of the Provost of Worcester College, Oxford, Asa Briggs. 'I wrote to him that I thought he was the greatest living painter.'2 But as both men realised that neither the paint encrusted studio nor the gruelling regular commitment would suit the busy schedule of Baron Briggs, Landau instead offered himself as a sitter. Auerbach cautioned,'My behaviour is disturbing and it might take two years.'3 Landau recalls,'He said he would if I was reliable and could sit on Fridays. I've been sitting on Fridays for 24 years.'4

Although the artist and sitter agreed to the weekly schedule which began in 1984, it would be two years of Friday morning sessions until one finished drawing was produced and not until 1987 that a painting in oil was deemed complete by the artist.

Landau's insights into the evolution of this portrait are even more revealing about Auerbach's general working methods. Over many years, the paint surface is scraped off, rebuilt, reshaped and 'sculpted', as if his raw material is modelling clay rather than pigment. After each sitting, he ruthlessly scrapes the paint off so that just a shadow of an image remains for the next session: 'It is a bit disturbing ... particularly on those occasions when you remember from the last time that the painting was quite good. You think this was a really beautiful picture and yet it wasn't good enough for him. Next time you arrive it will be a scraped-down ghost.'5

Eventually, there is a 'one take' finish, paint and fiery language flung about with heat-seeking accuracy. 'He has a physicality with his painting', Landau continues. 'He goes into a state of creative orgasm with all the signs of excitement, groans and screams. And he talks to himself all the time, saying "rubbish, it's not good enough, complete rubbish". But you realise that at some point in this act of creation he is suddenly being a little more content. He suddenly goes into a state of meditation and touches the canvas with great delicacy, and you think that maybe he has reached a stage where he is satisfied.'6

1. Sylvester, D., 'Young English Painting', The Listener, 12 January 1956

2. Jury, L., 'Auerbach & the Art of Painting', The Independent, London, 3 February 2007

3. The artist quoted in Feaver, W., Frank Auerbach, Rizzoli, New York, 2009, p. 21

4. Ibid.

5. David Landau quoted in O'Mahony, J., 'Frank Auerbach: Surfaces and Depths', The Guardian, 15 September 2001

6. Ibid.

WE ARE GRATEFUL TO DR PETER HILL FOR HIS ASSISTANCE WITH THIS CATALOGUE ENTRY.